Health

Unveiling the ‘Kiss of Death’: How Predatory Bacteria Eliminate Prey

- University of Nottingham researchers discover predatory bacteria’s ability to kill prey through a “kiss of death,” challenging previous understanding of its predatory behavior.

- The study, published in Nature Communications, sheds light on novel proteins involved in bacterial killing, offering insights for potential applications in healthcare, food safety, and environmental protection.

New research has found that a natural predatory bacteria, long known to target its prey by burrowing inside of them, is actually able to kill by delivering a ‘kiss of death, meaning it doesn’t have to live inside its prey to kill it, as previously thought.

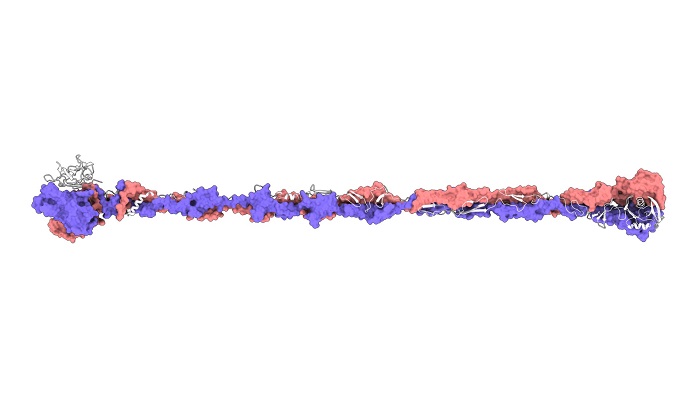

The new study, led by experts in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nottingham and published in Nature Communications, found that Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, when missing a special “MIDAS” adhesive molecule, is still able to apply a molecular “kiss of death” to bacteria, delivering predatory proteins that kill prey bacteria without the predator living inside them.

This reveals new biochemical details about the evolution of predation and new proteins involved in killing bacteria.

The discovery is another step towards scientists being able to use these predators to target and kill problematic bacteria that cause issues in healthcare, food spoilage and the environment.

The team in Nottingham used fluorescently coloured microscopy and genetics work, to show that a mutant form of the predator, with defects in a single adhesin, could sometimes fail to enter prey bacteria, but surprisingly still killed them. The use of different fluorescent colours allowed the team to locate the predatory bacteria while assessing the live or dead state of the prey bacteria.

Professor Andrew Lovering in the School of Biosciences, at the University of Birmingham, examined the structure of the adhesin and defined novel components of it specific to this behaviour. His data also guided team in Nottingham to test key amino-acids, associated with a MIDAS adhesin motif, which were found to be required for normal entry of the predator to prey.

Having seen that the predator could kill the prey without normal invasion, the team in Nottingham purified the empty but dead prey cells, testing for any predator proteins that may have been “kissed across” into them by the mutant predators who failed to enter.

The group of Bdellovibrio proteins found included some totally unstudied predator proteins, as well as proteins known to take part in bacterial killing during normal invasion.

Professor Liz Sockett, from the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nottingham, said: “This latest discovery of proteins will help our future understanding on what kills bacteria and how predatory bacteria evolved this toolset that kills prey.”

The research was carried out by Dr Jess Tyson and a team from Professor Liz Sockett’s lab in the School of Life Sciences at the University of Nottingham, including Rob Till. The team worked with Professor Andrew Lovering at the School of Biosciences at the University of Birmingham, on a joint project funded by the Wellcome Trust and collaborating on gene transcription with Dr Simona Huwiler at the Institute of Plant and Microbial Biology University of Zurich.

Source: University of Nottingham