Science & Environment

New Study Links Changes in Global Water Cycle to Higher Temperatures

- The Past Global Changes Iso2k project team, with Professor Matthew Jones at the University of Nottingham, used 759 paleoclimate records to reveal a historical connection between global temperature changes and shifts in the global water cycle.

- Their findings indicate that as the planet warms, water cycle changes are likely to increase, with potential implications for future rainfall and water availability.

An international group of experts from across the globe sought to investigate how water levels may be affected by changing global temperatures and used reconstructions from the past to try and predict future movements.

A study from the Past Global Changes Iso2k project team, including Professor Matthew Jones at the University of Nottingham, takes an important step toward reconstructing a global history of water over the past 2,000 years.

Using geologic and biologic evidence preserved in natural archives — including 759 different paleoclimate records from globally distributed corals, trees, ice, cave formations and sediments — the researchers showed that the global water cycle has changed during periods of higher and lower temperatures in the recent past.

“The global water cycle is intimately linked to global temperature,” said Bronwen Konecky, an Assistant Professor of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Washington University, and lead author of the new study published in Nature Geoscience.

“We found that during periods of time when temperature is changing at a global scale, we also see changes in the way that water moves around the planet,” she said.

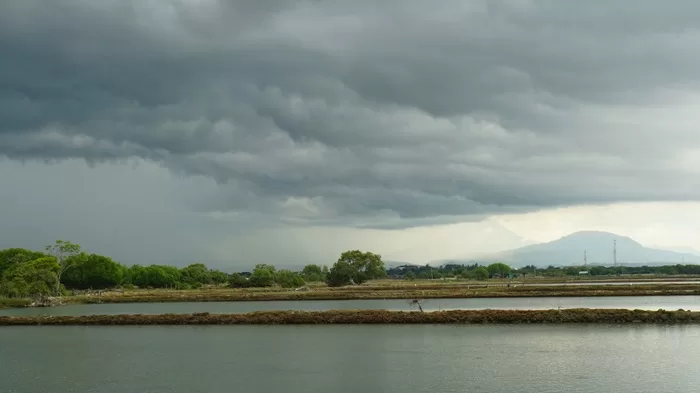

The water cycle is complex, and rainfall in particular has geographic variations that are much more drastic than air temperature. This has made it difficult for scientists to evaluate how rainfall has changed over the past 2,000 years.

With this new study, the scientists found that when global temperature is higher, rain and other environmental waters become more isotopically heavy. The researchers interpreted these isotopic changes and determined their timeline by synthesizing data from across a wide variety of natural archive sources from the past 2,000 years of Earth history.

The Iso2k project team — which includes more than 40 researchers from 10 countries — collected, collated and sometimes digitized datasets from hundreds of studies to build the database they used in their analysis. They ended up with 759 globally distributed time-series datasets, representing the world’s largest integrated database of water isotope proxy records.

Konecky added: “As the planet warms and cools, it affects the behaviour of water as it leaves the oceans and the vigour of its motions through the atmosphere. The isotopic signals in these waters are very responsive to temperature changes.”

When it comes to the specific impact of these changes on future rainfall and water availability, it is too early to predict who will win and who will lose. But this study’s data from the last 2,000 years suggest that more water cycle changes are likely as global temperatures continue to increase. June, July and August 2023 were the hottest months on record for our planet.

Professor Matthew Jones, from the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham, said: “Understanding how the global hydrological cycle responds to temperature change over different time scales, in terms of the potential magnitude and direction of change in different places, is critical for our understanding of what a future, warmer, world might look and behave like.

“Working with the PAGES Iso2k team to build this comprehensive global database of hydrological change over the last 2000 years or so, including many hundreds of individual records, and thinking about what it tells us about how the planet has changed has been an exciting opportunity to learn from scientists, and collective science expertise, from all over the world.”

Professor Matthew Jones, School of Geography

Source: University of Nottingham