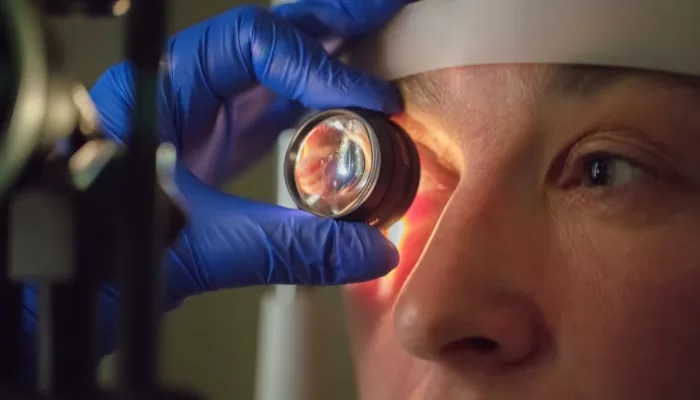

Health

Eye-Opening Discovery Offers Fresh Hope for Autoimmune Diseases Causing Blindness

- Scientists, including ANU researchers, discovered an uncommon TNIP1 protein mutation associated with autoimmune illnesses such as Sjogren’s syndrome and lupus.

- The mutation impairs the protein’s role in cell waste control, causing toxic buildup and immunological responses.

- The successful reversal of the mutation’s consequences in mice raises the prospect of more tailored pharmacological therapies and better treatments for those affected.

A multinational team of experts, including academics from The Australian National University (ANU), has made a significant advance in the understanding of autoimmune illnesses. They discovered a rare, mutant variant of a protein called TNIP1 that is associated with a persistent autoimmune illness comparable to Sjogren’s Syndrome. If left untreated, this illness, defined by acute dryness of the eyes and mouth, can result in serious problems such as blindness.

The TNIP1 mutation may also have a role in more serious autoimmune disorders, such as lupus, which is a debilitating condition that causes organ and joint inflammation, skin rashes, exhaustion, and, in severe cases, death.

The research team successfully reversed the detrimental effects of this mutation in mice, which is a promising start towards generating novel pharmacological therapies that could potentially benefit humans.

Dr. Arti Medhavy, principal author of the paper and a PhD graduate from ANU, emphasises the significance of this discovery: “This is the first time scientists have shown a variation of the TNIP1 protein is responsible for causing autoimmune disease in humans.”

Dr Medhavy, now with Griffith University’s Institute for Biomedicine and Glycomics, explains the role of TNIP1: “Proteins are critical to our growth, development and overall health, but they have a shelf life. Once the proteins have served their purpose, they become deactivated. That’s where TNIP1 comes in. It works in unison with the cell’s waste management system. TNIP1 essentially acts as a gatekeeper of the immune system by removing obsolete proteins and taking them to the cell’s degradation sites where they are broken down, recycled and repurposed.”

In a typical cell, genetic material is contained in particular compartments, including the cell’s energy manufacturers known as mitochondria. If this substance is found outside of these compartments, it can elicit an immunological response. “Importantly, TNIP1’s role in the waste management system includes the removal of damaged or leaky mitochondria, which helps maintain healthy cells. But the mutated version of the TNIP1 protein is less efficient at taking these waste proteins and mitochondria to be processed, leading to toxic build-up within cells. If this waste isn’t dealt with, these materials can become detrimental to the cell and trigger the immune system, which ultimately promotes the onset of autoimmune disease.”

Autoimmune illnesses impact almost one out of every ten Australians. Sjogren’s Syndrome alone affects around 270,000 Australians. Dr Vicki Athanasopoulos, a study co-author from ANU, emphasises the need for focused treatments: “There is a need to develop tailored treatments that specifically target the proteins and biochemical pathways that lead to the onset of autoimmune disease, rather than suppressing the entire immune system. There is currently no cure for autoimmune disease. Current therapies help patients better manage their condition, but these treatments have unpleasant side effects that make patients more susceptible to infection, which can lower their quality of life.”

The researchers identified the TNIP1 mutation in two unrelated patients, one from Australia and the other from China. Interestingly, although having the identical gene, the Australian patient had lupus symptoms, but the Chinese patient had evidence of Sjogren’s syndrome.

To conduct further research, the scientists used gene-editing techniques to implant the human TNIP1 mutation into mice. The mice experienced symptoms similar to those shown in the human patient suffering from Sjogren’s disease.

Dr Athanasopoulos notes, “The TNIP1 mutant protein is similar to the lupus-causing TLR7 mutation in that it affects the same biochemical pathway. There is work already underway by pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs and tweak existing ones that inhibit the TLR7 pathway.”

Dr Medhavy add’s, “Although both patients with the TNIP1 mutation had slightly different forms of autoimmune disease, they both had abnormally high levels of IgG4 antibodies in their blood. The abnormally high presence of IgG4 in both patients is interesting because clinicians might be able to use IgG4 as a biomarker of TNIP1-driven autoimmune disease. By screening patients with autoimmune disease for high levels of IgG4, clinicians might be able to test whether patients also possess the TNIP1 mutation, which would indicate that they may respond well to therapies targeting the same TLR7-pathway.”

This remarkable discovery paves the path for more precise and successful treatments for autoimmune illnesses, providing hope to countless people suffering from these terrible conditions.